Hellenism

As Alexander moved east, he replaced existing civic-leaders with Greeks from among his followers and in many cases created entirely new cities in places where only rough settlements had previously existed. An army on the move requires many resources and whatever can't be appropriated localy must be imported. Thus invasions create new trade routes and depots become cities along the way. In both cases the new leaders used their language (Greek) and their ideas about education (paideia) as a way of transforming (Hellenizing) the locals into people they could rule. Alexander's conquests are an early example colonialization, although the Greeks had a long-standing tradition of sending people off to live in nearby new (to them) lands whenever the existing settlement became over-crowded or some conflict led to separation or some environmental disaster necessitated moving. When Alexander died, his generals carved up the territory into principalities and paideia continued to flourish. Greek remained the language of education even after the rise of Rome.

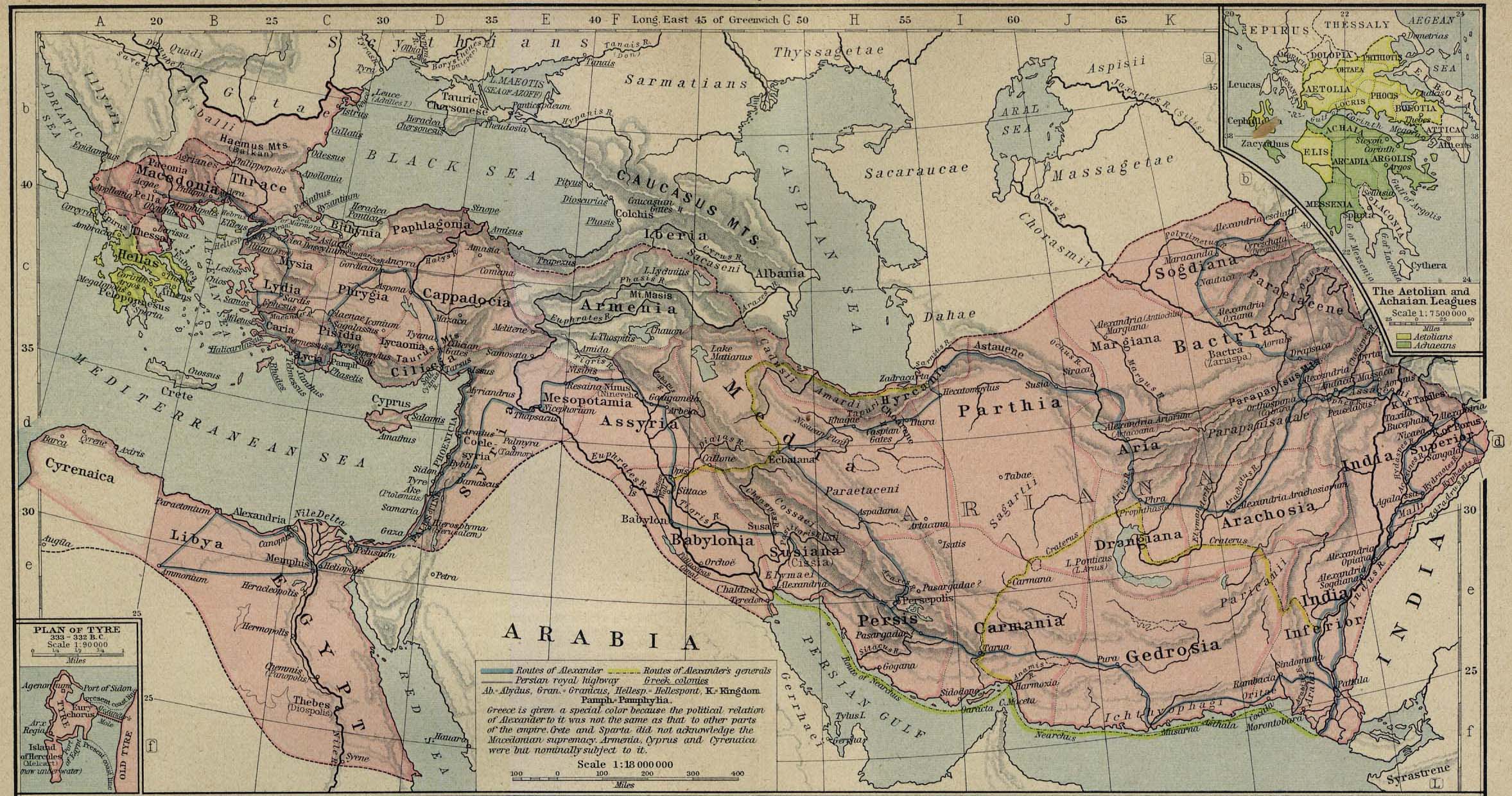

Map

Paideia : Grammar (interpretation of poetry), dialectic, rhetoric but also music and dance as well as gymnastics and wrestling. The ideal was a person fit to serve the city-state.

Paideia was considered a necessary requirement for any ambitious parent to bestow on their children, not just boys, but primarily as the girls often left early and were not expected to have a public role, though some did.

- Alexander died 323

- Aristotle died 322

- Anaximenes of Lampsacus died 320

- ...

- Cleopatra VII died 30 (a descendant of Ptolemy 1 who took over Egypt when Alexander died. She was Greek, not Egyptian more ...)

- Hermagoras of Temnos (fl. 1st century B.C.)

- Hermogenes of Tarsus (fl. 161–180)

- Rhetorica ad Herennium (80s B.C.)

Rhetoric ad Alexandrum

Written by Anaximenes of Lampsacus (c. 380 - 320), who was a contemporary of Aristotle and a rival of Isocrates. He too was one of Alexander's tutors. His importance to rhetoric is at least two-fold. He demonstrates that Aristotle wasn't working in a vaccuum. He also offers the first mention of the prgymnasmata, the exercises preliminary to declamation (Ch 28).

Stasis Theory

Invention and arrangement. What questions to answer and what order to ask them in as well as what method leads to indisputable answers. We see stasis for the first time in Book 3 of Aristotle's rhetoric and it is dealt with by many subsequent rhetoricians, often with increasing complexity. See Classical Systems Of Stasis In Greek: Hermagoras To Hermogenes

"Hermogenes of Tarsus (fl. A.D. 170) wrote the most thorough exposition On Stases... that has come down to us from ancient times" (Ray Nadeau, p 66)

Rational disagreement requires an issue, different answers to the same question. Same answer to the same question means there is no issue and therefore no need for an argument. Disagreement about what the issue is requires securing an agreement before rational disagreement can happen. Thus they rely on agreement about what is a fact, what is merely an assertion, and when method of inquiry can turn an assertion into a fact.

Contentious arguments, ones that are unlikely to lead to insights or decisions, are based on disagreements about what counts as a fact (evidence) and how facts are obtained (methodology). They often differ on the fundamental premises from which they draw conclusions, define the same words differently or have differing connotations associated with the same words, and thus rely on a different set of enthymemes and maxims. They also often have different vivid examples (Aristotle's paradigms) in mind from which they draw conclusions about new events. Everyone has availability bias, but different people have different evidence available. The culture wars are actually rhetorical wars, asystatic controversies used to galvanize voters. They use rhetoric as a weapon against rhetorical discision making.

For any given rhetorical situation you can create a stasis map, 1) a set of questions you need answered 2) asked in the order they need to be answered 3) and a method for deciding when they have been answered. To the extent a rhetorical situation can be generalized an existing stasis map can suffice. However, overlaying an existing stasis map on top of a unique rhetorical situation may distort one's understanding of the situation. Before you apply a template, look closely at the material.

Death of a person:

- Natural death or homicide?

- If natural, stop

- If homicide, then

- Who did it?

- (motive, means, opportunity)?

- Once suspect identified, then

- Did this person kill that person?

- If yes, then

- Murder or manslaughter?

- if premeditated, then murder.

- if reactionary, then crime of passion or self-defense?

- if accidental, then negligent or tragic?

Memory

Rhetorica ad Herennium (c. 80s) From Wiki: "the oldest surviving Latin book on rhetoric, dating from the late 80s BC, and is still used today as a textbook on the structure and uses of rhetoric and persuasion."

Progymnasmata

As Wiki has it, "There are only four surviving handbooks of progymnasmata, attributed to Aelius Theon (mid to late 1st century ad), Hermogenes of Tarsus (flr AD 161–180), Aphthonius of Antioch (4th c. ad or later), and Nicolaus the Sophist." Thus in a sense it belongs to the Second Sophistic, but since it appears as early as The Rhetoric ad Alexandrum, it belongs under the heading of Hellenistic rhetoric as well. Each of the 14 exercises is worth studying on its own, though we don't have time to do this here.

Heath's translation of Apthonius' Progymnasmata

For next week

- Second sophistic

- Progymnasmata if we didn't get to it today

- Declamation

- Seneca's introduction

- Pseudo Quint's Oration X