Hellenistic Rhetoric

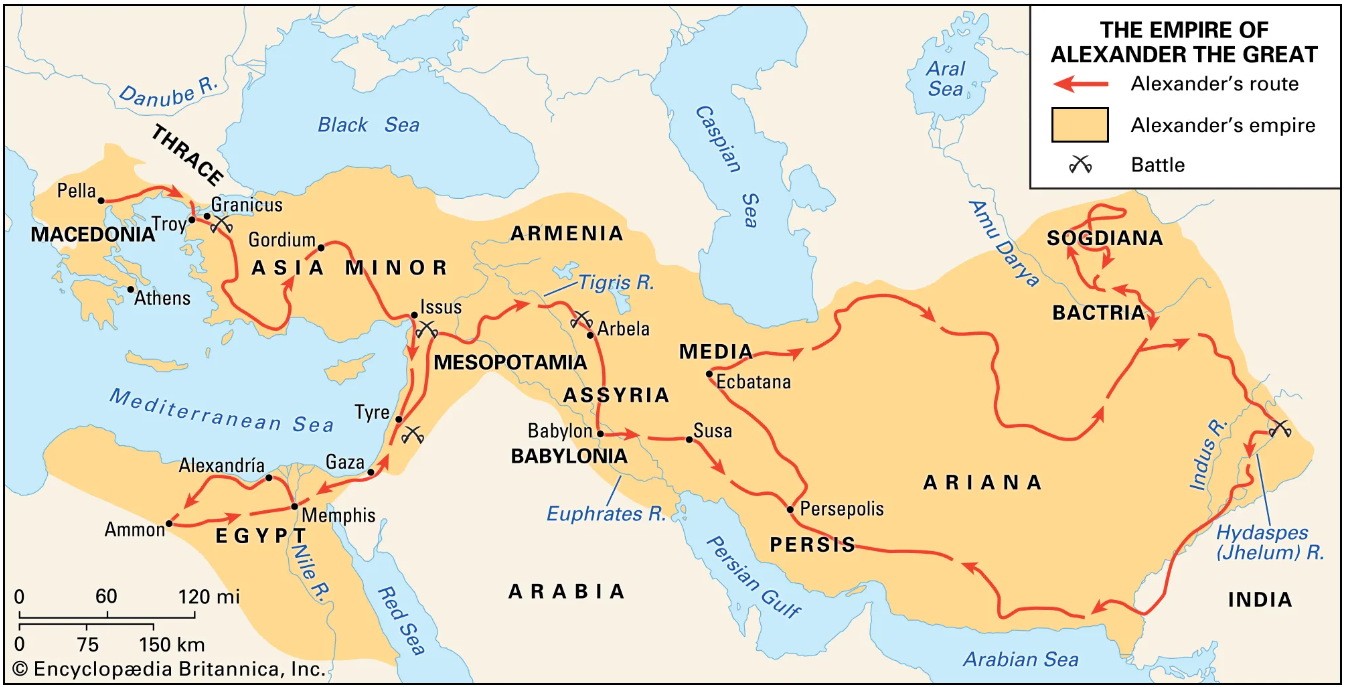

Map of Alexander's Empire: Land of Greek Paidea

Generally speaking, See "Periodicity and Scope" in The Oxford Handbook of the Second Sophistic to better understand why I open this section with such a hedge. the Hellensitic period refers to life in the Mediterranian from the Death of Alexander (323) Claude: Here is a bullet point overview of Alexander the Great's rise to power, conquests, death, and the 50 years after:

* Born in 356 BC in Pella, Macedonia, Alexander was tutored by Aristotle and raised by his father, King Philip II.

* At age 16, Alexander became regent when his father left for a military campaign. He put down rebellions in Macedonia and defeated the Thracian tribes.

* In 336 BC, at age 20, Alexander became king of Macedonia after his father was assassinated.

* Alexander conquered the Persian Empire between 334-323 BC, defeating Darius III and advancing as far east as India. His empire spread from Greece to Egypt to India.

* Major battles included Granicus (334 BC), Issus (333 BC), Gaugamela (331 BC), and Hydaspes River in India (326 BC).

* Alexander died suddenly in Babylon in 323 BC at age 32. The cause of his death is uncertain - possibly illness, poison, or infection.

* After Alexander's death, his generals (Diadochi) fought over control of the empire, dividing it into kingdoms ruled by Alexander's former generals.

* The major successor kingdoms were the Seleucid Empire, Ptolemaic Egypt, Macedonia, and Pergamon. This period marked the beginning of the Hellenistic Age.

* Over the next 50 years after Alexander's death, the successors consolidated their power and expanded their territories through wars and alliances.

* The empire was weakened by infighting and gradually succumbed to Roman power over the next few centuries. Alexander's conquests spread Greek culture far and wide.

to the death of Cleopatra (30) Claude:

Here is a bullet point overview of the life of Cleopatra:

* Born in 69 BC - Member of the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt after Alexander the Great

* Became queen of Egypt in 51 BC when she was 18, ruling jointly with her brother Ptolemy XIII

* Aligned herself with Julius Caesar in 47 BC during Roman civil war; became his lover and bore him a son, Caesarion

* After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, she aligned with Mark Antony, having twins with him

* Battled for control over Roman territories with Octavian, Caesar's heir - Their forces were defeated at Actium in 31 BC

* Committed suicide in 30 BC by allowing herself to be bitten by a snake rather than be captured by Octavian

* Her death ended the Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years

* Cleopatra was known for her intelligence, ambition, and romantic/political alliances with powerful Romans

* She was one of the most famous female rulers of antiquity and remains an iconic figure today

, after the Battle of Actium,

Claude:

Here is a bullet point overview of the Battle of Actium in 31 BC:

* Fought between forces of Octavian and the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra

* Took place near Actium on the western coast of Greece

* Octavian's fleet was led by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa while Antony's fleet was commanded by Gaius Sosius

* Antony's forces were estimated to be around 230 ships while Octavian had about 400 ships

* Cleopatra was present with her own fleet - her sudden departure during the battle was a pivotal moment

* Octavian's forces were able to defeat Antony's fleet, which suffered major losses

* Following this defeat, Antony and Cleopatra retreated to Egypt

* Octavian invaded Egypt the next year, leading to defeat, the suicide of Antony and Cleopatra, and Roman control of Egypt

* The battle marked the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire under Octavian, later called Augustus Caesar

* Octavian became the first Roman emperor - Actium allowed him to consolidate his power over the Roman world

in which Mark Antony's naval fleet was defeated by Octavian's and Rome ceased to be a Republic and became an Empire:

The empire of Alexander and its Successor kingdoms spread the use of the Greek language far more widely through the eastern Mediterranean world than had been the case previously and engendered the development of a koinë (literally common) Greek that became the lingua franca in these newly Greek-speaking areas and in some parts of Asia Minor where Greek had been in use for centuries. Largely for that reason, the period from Alexander's death (323) to the incorporation of the last independent Greek-speaking kingdom into the Roman empire with the death of Cleopatra VII (30) is known as the Hellenistic period. The proliferation of the Greek language encouraged a simultaneous introduction of other aspects of Greek culture, including the study of rhetoric. In consequence, individuals and communities in the eastern Mediterranean world began to contribute to the development of rhetoric in the areas of both theory and practice. Naturally, the successors to the practitioners of rhetoric in Classical Greece, especially at Athens, continued to think and write about their field of study during the Hellenistic period, but these were no longer the sole proprietors of their craft, either in establishing the rules or in delivering the most important speeches. Of course, even in Classical Greece, some of the best orators had not been of Athenian origin (for example, Gorgias of Leontini) Nevertheless, Athens (to our knowledge) was the focal point for rhetorical theory and practice: most extant classical speeches (as well as most theory) are somehow connected to Athens. John Vanderspoel. A Companion to Greek Rhetoric, Ed. Ian Worthington. Blackwell 2007

As Rome conquered neighboring cities, tribute in the form of taxes and slaves poured into the city. The wealthy acquired more opportunities to enhance their wealth and new ways to display it, in the form of bigger houses and imported furnishings and a retinue of household slaves. One of the most prestigious symbols was a Greek pedagogus (a child leader), a slave whose sole responsibility was to look after the male heir, to walk with him to school to keep him out of trouble (and away from trouble) and to help him with his homework, all the while teaching him Greek and Grecian sophistication. Other Greeks, educated and not so much, also found their way to Rome as so many other peoples in the region did, because "All roads lead to Rome." They came looking for work or stayed after they had worked off their indenture. In Rome as it was sometimes in Greece you could forfeit your freedom if you owed money. This is still true in some parts of America today where you might be incarcerated for not paying your parking fines. But in the past your forfeit was owed directly to the individual you owed money to and you might end up working in their household or on their lands or you might be sold to a broker or another wealthy individual. Slavery wasn't necessarily a permanent condition. Even those enslaved via capture in battle might be liberated by a grateful and usually deceased owner.

The Romans were ambivalent about Greek culture. On the one hand, they had an oft-told tale about how they descended from Aeneous, Prince of Troy, who fled into the wilderness when Troy fell and eventually landed at the mouth of the river Tiber, where he married a local woman and together they begat the people who became Rome. On the other hand, the Empire built by Alexander, which had spread Greek education and language from one end of the known world to the other, and up and down, had disintegrated after his death, leaving a vaccum needing to be filled, and when Rome finally defeated and annihilated Carthage, in 146 BCE, she took as spoil the entire Mediterranean and thus the Greek language, education, and culture that Alexander had left undefended. Because everyone already spoke koinë, it was more efficient for Romans to learn Greek than for everyone else to learn Latin, at least in the short term. Moreover, the Romans didn't have a system of education to replace paideia, and so they simply adopted it.

And yet, of course, Latin was Rome's native language. The most nationalistic (patriotic?) Romans resented Greek culture (paideia). The harshest critics considered learning the language and literature and oratorical practices and preferences of a beaten and displaced people beneath the dignity of the conquerors of the world, although it's likely even they knew well what they rejected because they would have been schooled in paideia as youngsters. One of the characters in Cicero's De Oratore (Marc Antony, the grandfather of Marc Antony, the infamous, no less), expresses derision of Greek learning while indirectly demonstrating a thorough knowledge of it.

Many less patriotic (and landed) people found Greek education, specifically philosophy and rhetoric, both intriguing and potentially profitable, an avenue to financial and political success. Because Greek was the language of commerce and travel, it was a source of wealth and sophistication, and because Greek required money and time and effort to learn, speaking and reading it was a mark of social distinction, much as Latin was later prized among the educated in Northern Europe and French was in St. Petersburg. I suppose if there were an equivalent in America today it would be computer languages, perhaps Python or R. I am only partially kidding.

One of the rhetorical manifestations of this reverence/ambivalence for Greek culture was known as "Atticism," the conviction that the best Greek was that as it was spoken by Athenians at the height of Athenian hegemony. There were 10 Attic orators Aeschines

Andocides

Antiphon

Demosthenes

Dinarchus

Hypereides

Isaeus

Isocrates

Lycurgus

Lysias

in particular who were said to have spoken the "purest" Greek. They became the models for generations and some people thought that if a word did not appear in what any of these 10 were recorded as saying, then it wasn't worth uttering. The Attic style was plane and forceful. It was contrasted with the "Asiatic" style, said to come from Rhodes, east of Rome, which was ornamental and given to flourishes of figures and emotional appeals. This struggle between styles seems to have reached its peak in the second sophistic, the first and second and third centuries of our common era, but Cicero mentions it -- siding with the Atticists and yet speaking in a highly dramatic fashion, suggesting Rhodian influence.

That a pseudo controversy over taste as displayed in an increasingly archaic language could occupy so many people for so long is a curious facet of education. You can't be great unless you have enemies, as the saying goes, because by rhetorical convention you shouldn't speak without cause: Cicero observes that "speaking itself is never anything but foolish, unless it is necessary" (De Orator, 83). Thus manufacturing enemies was a standard ploy. Many sophists of the second wave use rivalry and antagonism to lift their intellectual profile, I suppose as East and West Coast rappers did in the early 90s of our culture. The "War on Christmas" is another example of manufactured antagonism. If you want the other kids to pay attention to you, pick a fight.

Rome was a volatile place and when things got ugly, any possible source of unrest might be crushed with armed guards, whether senatorially sanctioned or privately funded. Foreigners often bore the brunt of these crack downs and twice the Greek teachers were expelled from Rome. Those Romans who liked to mythologize themselves as having come from the land, hard working agrarians who preferred practical skill to refinement and politics, preferred the plain style to the grand style. They were carefully on guard against sounding too Greek, Eastern or Asiatic.

"In the Epoch preceding our own, the old philosophic rhetoric was grossly abused and lamented that it fell into a decline. From the death of Alexander of Macedon it began to lose its spirit and gradually wither away, and in our generation had reached a state of almost total extinction. Another Rhetoric stole in and took its place, intolerably shameless and histrionic, ill-bred and without a vestige either of philosophy or of any other aspect of liberal education. Deceiving the mob and exploiting its ignorance, it not only came to enjoy greater wealth, luxury and splendor, than the other, but actually made itself the key to civic honours and high office, a power which ought to have been reserved for the philosophic art. It was altogether vulgar and disgusting, and finally made the Greek world resemble the houses of the profligate and the abandoned: just as in such households there sits the lawful wife, freeborn and chaste, but with no authority over her domain, while an insensate harlot, bent on destroying her livelihood, claims control over the whole estate, treating the other like dirt and keeping her in a state of terror; so in every city,the highly civilized ones as much as any, the ancient and indigenous Attic Must, deprived of her possessions, had lost her civic rank, while her antagonist, an upstart that had arrived only yesterday or the day before from some Asiatic Death-hole . . claimed the right to rule over Greek cities, expelling her rival from public life. Thus was wisdom driven out by ignorance, and sanity by madness" (Dionysus of Halicarnassus, "The Ancient Orators", 5)

Both in tone (florid) and content (melodrama), this Dionysian sensationalism exemplifies the Roman ambivalence about Greek culture, the irony of Dionysus being an Eastern Greek adding greatly to the overall effect. The domina (rightful mistress of the Roman home -- domicile) has been usurped by an Eastern whore. Athens is east of Rome and Rhodes and Halicarnasus are east of Athens) The dominus, presumably, was complicit or perhaps somehow he just didn't notice. This melodrama also exquisitely prefigures Second Sophistic rhetoric, declamation in particular, as we will see.

Key Concepts

- Hellenism

- Koinë (literally common) Greek -- enabled commerce, travel, and paideia, the spread of rhetorical performance as a mark of social distinction

- Mnemonics: Simonides of Ceos' Memory Palace

" The statue of Ricci in downtown Macao, unveiled on 7 August 2010, the anniversary of his arrival on the island " (link)Interesting sidebar: The memory palace idea was imported into Ming dynasty China in 1577 by a cartographer and missionary named Matteo Ricci. See, Jonathan D. Spence, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci. Matteo wrote a book explaining the idea of a memory palace for the Emperor's sons, who apparently thought it ingenious but unwieldy, requiring as it did an apparatus more complex than just endless repetition. For more on memory, see Memory Techniques Wiki.

- Paideia - Greek enculturation in the diaspora

- Stasis Theory

Significant People and Texts

- Rhetoric ad Alexandrum (344 bc) is, strictly speaking, prior to Hellenism, but it deserves early mention because it was the first classical text to mention Progymnasmata the 14 progressively more difficult exercise syllabus that came to have a central place in subsequent rhetorical pedagogy chapter 28 is first mention of progymnasmata.

- Digital version Rhetoric ad Alexandrum

- Theophrastus (371 – c. 287 BC) Wiki article, Aristotle's successor, was a polymath, like Aristotle. His direct relevance to rhetoric is book called "On Characters" which we still have.

- Rhetorica Ad Herennium (late 80's BCE), the oldest surviving rhetoric handbook in Latin. Although there is little innovative about it, it does offer the oldest known rhetorical explanation of memory and that is definitely worth reading

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. 60 BC – after 7 BC), an historian and teacher of rhetoric, a contemporary of Augustus Caesar. He was an atticist. On Literary Composition.

- Seneca the Elder (54 BCE – c. 39 AD) spans, as it were, two periods of rhetorical history. He was born at the end of the Hellenistic period and died 9 years in to the Second Sophistic. Periods, after all, are only rough estimations and open to debate and interpretation. Seneca the Elder, however, is critical to the history of rhetoric because it is from him and only two others (the pseudo Quintilian and Cornelius Flaccus) that we get a clear image of declamation, the ultimate rhetorical exercise which had it's highpoint during the second sophistic but was a practice Cicero was familiar with. It's importance as a rhetorical training apparatus stretched into the 19th and perhaps even the early part of the 20th century. I've excerpted the introduction to his collection of Suasoria and Controversia

Secondary Sources

Caplan, Harry. "The Decay of Eloquence at Rome in the Fist Century." Of Eloquence in Ancient and Medieval Rhetoric. Ed. Anne King and Helen North. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1970. pp 160-95.

Clarke, Donald Lemon. Rhetoric in Greco-Roman Education. New York: Columbia UP, 1957.

Clarke, M. L. Rhetoric at Rome: A Historical Survey. 3rd edition. London: Routledge, 1996.

Enos, Richard Leo. Roman Rhetoric: Revolution ad the Greek Influence. Waveland: Prospect Heights, 1995.

Graziosi, Barbara, Phiroze Vasunia, and George Boys-Stones. Eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies. Oxford UP, 2009.

Jaeger, Werner Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, vols. I-III, trans. Gilbert Highet, Oxford University Press, 1945.

Kennedy, George A. The Art of Rhetoric in the Roman world, 300 B.C.-A.D. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

Marrou, Henri Irenee. A history of education in antiquity University of Wisconsin Press, 1982. Chapter 11, "The Educational Institutions of the Hellenistic Age (Google Books), is especially relevant.