Given that AI text generators can, if correctly prompted, write useful, humanesque prose, to say nothing of producing competent translations and useful computer programs, composition teachers face a significant dilemma. I can think of five approaches.

Machine learning requires human input and supervision initially. Several famous authors have sued, arguing that their work was used as training material without permission. Google has enlisted millions of unidentified users to unknowingly help train image recognition via Captcha. AI companies have also used Amazon's Mechanical Turk business to harness thousands of anonymous, low-paid workers in the service of tagging text for LLM learning. As more people become aware of how exploitive the creation of LLMs has been, more litigation is inevitable.

legislation, Italy temporarily banned ChatGPT ([1]), The EU plans to regulate AI [[2], and the US senate has recently held hearings that might lead to legislation [3]. Other countries are no doubt considering legislation as well., social and labor activism, The tremendous environmental, social, and economic cost of LLMs when measured against their still uncertain ROI might cause a market exodus, while fear of AI taking over "content creation" might lead to union-imposed constraints.

profit-taking Anthropic recently announced it is looking at a $50 a month paid version. ChatGPT has offered a $20 subscription version for some time now and just introduced an enterprise tier. Micro Soft is thinking, I read somewhere, of charging an extra $30 a month for its AI enhanced office suite. And yesterday Google announced an enterprise plan of $30 per person for AI in Gmail, Duet, and Google Workspace. Seems like the beta era is over and it remains to be seen how hobbled the free versions will be. or some combination may eventually wall off access

Machine learning requires human input and supervision initially. Several famous authors have sued, arguing that their work was used as training material without permission. Google has enlisted millions of unidentified users to unknowingly help train image recognition via Captcha. AI companies have also used Amazon's Mechanical Turk business to harness thousands of anonymous, low-paid workers in the service of tagging text for LLM learning. As more people become aware of how exploitive the creation of LLMs has been, more litigation is inevitable.

legislation, Italy temporarily banned ChatGPT ([1]), The EU plans to regulate AI [[2], and the US senate has recently held hearings that might lead to legislation [3]. Other countries are no doubt considering legislation as well., social and labor activism, The tremendous environmental, social, and economic cost of LLMs when measured against their still uncertain ROI might cause a market exodus, while fear of AI taking over "content creation" might lead to union-imposed constraints.

profit-taking Anthropic recently announced it is looking at a $50 a month paid version. ChatGPT has offered a $20 subscription version for some time now and just introduced an enterprise tier. Micro Soft is thinking, I read somewhere, of charging an extra $30 a month for its AI enhanced office suite. And yesterday Google announced an enterprise plan of $30 per person for AI in Gmail, Duet, and Google Workspace. Seems like the beta era is over and it remains to be seen how hobbled the free versions will be. or some combination may eventually wall off access

I prefer option five, although even so I encourage students to document the process they used to write anything substantial they turn in for grade. A weekly progress report on sites.gsu.edu is one simple way to help students stay focused, share their progress, and give their teachers the opportunity to see where a final product came from.

This website is offered as a primer on how to teach composition in the era of AI text generation. Its goal is to advocate for building AI text generation into both how we write and how we teach others to write. It also seeks to advance the idea that prompt-crafting is a new rhetorical genre, one that needs to be both studied and taught in any writing intensive class. This is not to say that we need to learn how to teach machines to write (or speak) for us, but rather that we need to learn how to use them to facilitate our own thinking and writing while also learning how to critique what they write so as to avoid perpetuating lies and mis-information.

Ironically,

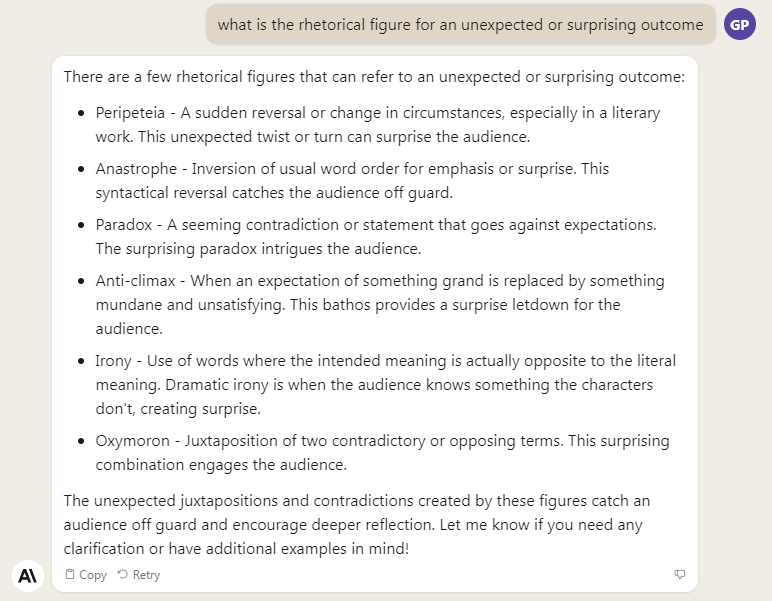

The correct rhetorical figure here is Peripeteia, as Claude helped me remember AI text generators use highly sophisticated statistical models and hundreds of gigabytes of text scraped from the Internet -- as well as human supervision at least initially

A Jargon Free Explanation of how Large Language Models Work -- to do what the sophists did from memory and practice.

If you (or your machine) can identify the relevant pattern, you know what you need to say next. That people have learned how to get machines to generate text worth reading is astounding. The implications of the accomplishment are profound, unsettling, disruptive. People who write for a living, regardless of job title, will need to write more efficiently and those who rely on old (not AI-assisted) writing processes will under-perform.

So we need to experiment with these tools, learn what they can and cannot do for us, while helping our students do the same for themselves.

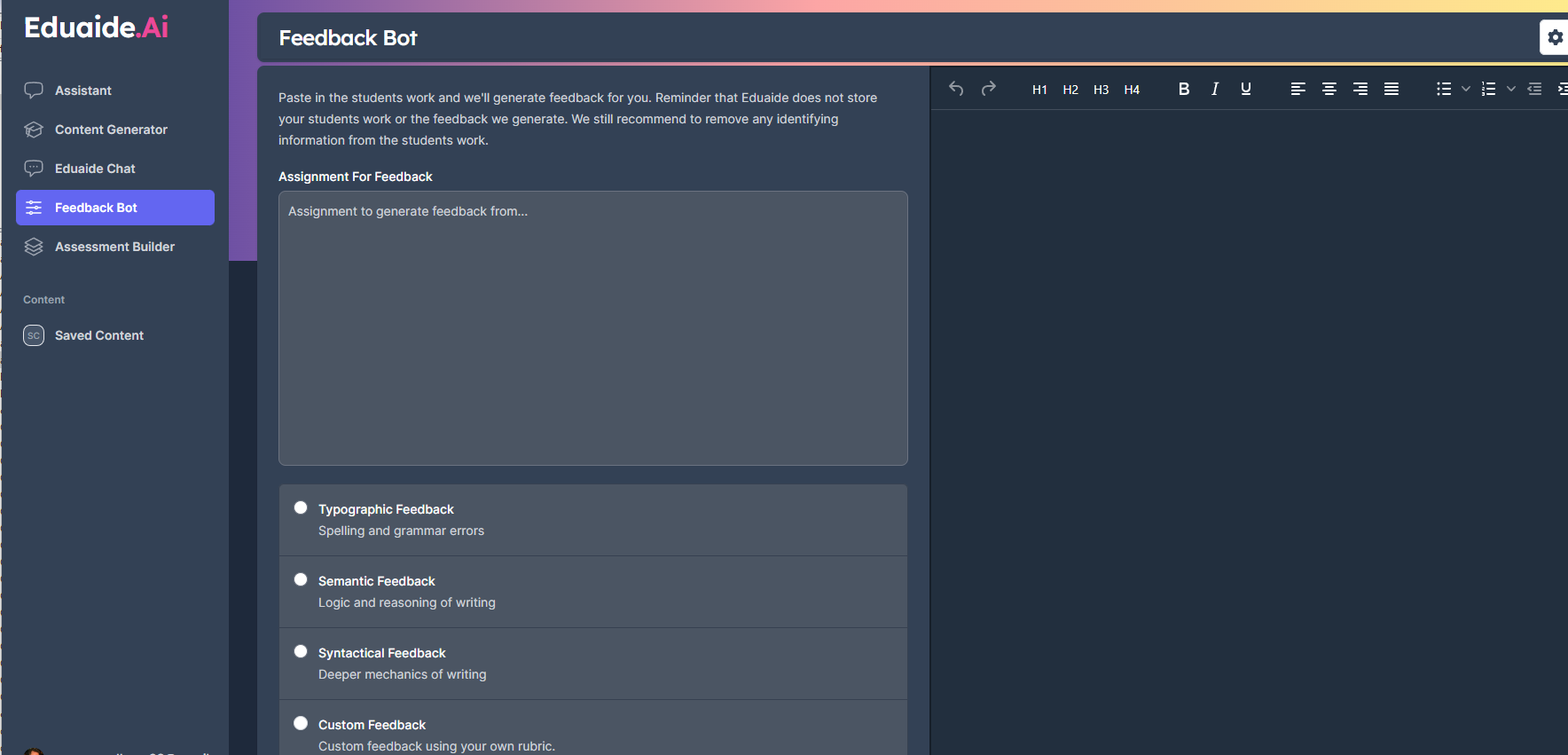

There are companies and educators working on AI tools to automate the process of providing student feedback. One, Eduaide.Ai, has a

copy and paste panel

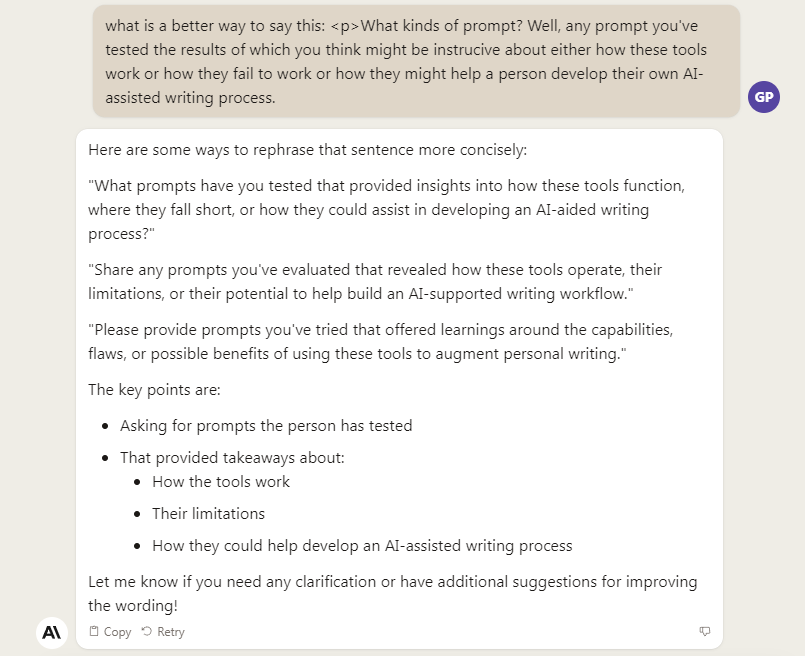

If you would like to share a successful ai-informed writing prompt, please click on the Assignments/Share an assignment menu link. If you want to join a work-group pondering all of this, please email George Pullman (gpullman@gsu.edu).

What kinds of prompt? Well, any prompt you've tried that revealed how these tools opperate, their limitations, or their potential to help build an AI-suppoted writing workflow.

from a historian of rhetoric's perspective, the latest technological marvel merely automates an ancient sophistic discipline. Give me a topic, any topic, and I'll give you a speech on the spot, we were told Gorgias proclaimed (Gorgias, [448a]). From then on, in the Western European educational tradition, memorizing what others said, discovering and collecting topics and patterns of thought, forms of expression, and characterizations of people became how one learned first to speak in public and later to write for important causes. People trained in this kind of rhetoric knew what an accomplished speaker would likely say next because they knew what the options were, the way a great athlete knows where the ball is going before it goes there. The rhetorically innocent weren't familiar with the patterns and forms and so mistook craft for reality or magic. Plato, borrowing Socrates' voice, complained that the sophistic rhetoricians didn't really know what they were doing and their advice was based on nothing more than tradition and prejudice. He warned people not to listen to sophisticated nonsense. He also advised us to reject literacy on the grounds that words written down were the illusion of thought, a shadow, a misleading facsimile of communication and knowledge. Plato Phaedrus 274c-277a

from a historian of rhetoric's perspective, the latest technological marvel merely automates an ancient sophistic discipline. Give me a topic, any topic, and I'll give you a speech on the spot, we were told Gorgias proclaimed (Gorgias, [448a]). From then on, in the Western European educational tradition, memorizing what others said, discovering and collecting topics and patterns of thought, forms of expression, and characterizations of people became how one learned first to speak in public and later to write for important causes. People trained in this kind of rhetoric knew what an accomplished speaker would likely say next because they knew what the options were, the way a great athlete knows where the ball is going before it goes there. The rhetorically innocent weren't familiar with the patterns and forms and so mistook craft for reality or magic. Plato, borrowing Socrates' voice, complained that the sophistic rhetoricians didn't really know what they were doing and their advice was based on nothing more than tradition and prejudice. He warned people not to listen to sophisticated nonsense. He also advised us to reject literacy on the grounds that words written down were the illusion of thought, a shadow, a misleading facsimile of communication and knowledge. Plato Phaedrus 274c-277a

[Writing] will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise. He may have been right. We literates will never know. It doesn't matter. But here we are again, on the cusp of an intellectual revolution. People born today won't read or write or learn or think they way we do.

that purports to offer semi-tailored feedback to share with students. Tools like these will become more and more prevalent. But we needn't wait because we can develop our own prompt-libraries, collections of prompts that a person can use to invent, draft, revise, and edit at a higher level and a quicker pace. These will be free for our students and we will be able to tailor them for our own specific contexts, disciplinary and social.

that purports to offer semi-tailored feedback to share with students. Tools like these will become more and more prevalent. But we needn't wait because we can develop our own prompt-libraries, collections of prompts that a person can use to invent, draft, revise, and edit at a higher level and a quicker pace. These will be free for our students and we will be able to tailor them for our own specific contexts, disciplinary and social.